From August 4 to September 2, 2020, I (Matt, creator of DIY Packraft) hiked and paddled from one end of Vancouver Island to the other.

Watch the highlights video below, or scroll down to read a day-by-day account of this trip.

Vancouver Island Geography

Vancouver Island is a large island off the west coast of North America, near the border between Canada and the United States. The nearest large cities are Vancouver (Canada) and Seattle (USA). The island is approximately 455 kilometers (283 miles) long, and the geography is similar to that of New Zealand’s South Island: steep-sided valleys, lakes, and fjords, with a mountainous central massif featuring dozens of glaciers, and a somewhat dryer and flatter east coast. Like the coasts of Washington and Oregon to the south, the west coast of Vancouver island is a mix of rocky shores, cliffs, and vast sandy bays. Prevailing winds from the west bring rain from the Pacific Ocean, and Vancouver Island is home to the wettest place in North America – Henderson Lake – where 9,307 mm (366.4 inches) of rain fell in 1997. Most of the island is covered in temperate rainforests, featuring some of the world’s largest Sitka spruce, Western Red cedar, and Douglas fir trees, among others.

Due to the tremendous amount of precipitation that falls as snow at higher elevations, snow persists in the mountains late into summer, and alpine tundra starts at relatively low elevations (about 1000 meters or 3000 feet above sea level). The highest point on Vancouver Island is only 2195 m (7201′), but with steep terrain rising from valley bottoms barely above sea level, the peaks have characteristics of much taller mountains.

Vancouver Island’s forests are notoriously dense and difficult to penetrate once a hiker strays off an established route (the local Alpine Club named their newsletter the “Island Bushwhacker”), and at times during my trek I resorted to crawling on my hands and knees because the foliage was so thick I could not push through it standing up.

Nearly all of Vancouver Island’s human population lives on the relatively dry southeast coast, and the vast majority of the landmass is uninhabited public land, only accessible through a maze of gravel logging roads.

Vancouver Island Wildlife

Vancouver Island is home to the world’s highest concentration of cougars (mountain lions), but they are seldom seen and rarely attack people. Grey wolves live on the island, but they are also shy. Black bears, on the other hand, are frequently encountered in the backcountry (but are generally not aggressive). Elk herds can be found on some parts of the island, and deer are ubiquitous at lower elevations.

Unlike on the mainland, grizzly bears, moose, coyotes, lynx, and bobcats do not live on Vancouver Island. There are no venomous snakes there either, and aside from black widow spiders (which I never saw in over 30 years of living on the island), I’m not aware of any other venomous animals on the island. I’m also not aware of any shark attacks being reported in the waters around Vancouver Island, though great whites, makos, and other large sharks are found there.

Marine mammals that are commonly seen near shore include orcas (killer whales), grey whales, seals, sea lions, porpoises, river otters, and the endangered sea otter. Several other whale species also live in or transit through the waters around Vancouver Island.

Salmon spawn in Vancouver Island’s rivers, and many of the lakes contain trout and other freshwater fishes.

Why this Challenge?

I grew up on Vancouver Island and learned to hike, camp, and paddle there, so it has always been a special place for me; in addition, I think its rugged coastline, giant trees, clear lakes and rivers, and snow-capped mountains are objectively beautiful.

Around the year 2000 I attended a presentation given by someone who had attempted to hike from one end of the island to the other (I wish I could remember his name), and it inspired me to try it myself. I hadn’t heard of packrafts at the time, and I thought hiring a boat to take me across the waterways would be cheating, so I plotted a route entirely on land. I set out with my friend Lara, but I was physically unprepared and I had to abandon the attempt after only five days due to foot and knee injuries. Lara flew to Spain to walk the Camino de Santiago instead while I sat at home and sulked about my failure. In the years that followed, it felt like unfinished business, and every once in a while I would start looking at maps and dreaming about the day I would try again.

In 2015 I was looking at all the lakes and fjords that cut off many of the potential hiking routes and I thought, “What if I had a lightweight boat that I could carry with me? That would open up some new possibilities!” I started looking around online and I discovered packrafts, which seemed like the perfect solution, but they were much too expensive for me. “But maybe I could make a packraft myself,” I mused. After much trial and error, that thought turned into DIY Packraft.

I got sidetracked for a few years refining my packraft designs, but eventually I started seriously planning the trek, and after a couple of years of research and preparation, I was ready to begin.

My Gear

I’ve created a separate page with my gear list and reviews of some of the most important items (I’m still working on it).

The Route

To travel from one end of Vancouver Island to the other entirely by foot and packraft, one could choose from a nearly infinite set of possible routes. I created mine by first drawing the longest straight line possible on Vancouver Island (from Gonzales Point at the southeast end of the island to Cape Scott at the northwest end) and then, with the start and end points decided, I picked a number of highlights and points of interest I wanted to see along the way, such as the West Coast Trail, Henderson Lake (the wettest place in North America), Della Falls (the tallest waterfall in North America), the Golden Hinde (the island’s tallest mountain), and the Nimpkish River (the island’s longest river). I then studied maps and satellite imagery and slowly began to figure out ways to link these points together by paddling on lakes, rivers, and inlets, and by hiking on established trails, ridge routes, remote logging roads (some active, some overgrown), and bushwhacking.

I avoided cities and towns as much as possible, instead relying on caches of food and equipment that I buried along my route in the days before I began the trek. After leaving the more populated southeast end of the island on Day 4, the most populous place I passed through was Gold River, a remote town of 1267 people, where I rested on Day 18. After that, the only population centers I passed through were Woss (pop. 200), where I did not stop, and Holberg (pop. 35), where I was greeted like a long-lost relative and given a hot meal, a warm shower, cold beer, and a dry place to sleep thanks to Pat, owner of the Scarlet Ibis Pub.

Unfortunately the world famous West Coast Trail (WCT) in Pacific Rim National Park was closed for the season due to COVID-19, so I had to change my route just weeks before my start date (Parks Canada made it very clear that it was illegal to set foot on the trail during the closure). Fortunately I had already hiked the WCT once before, and I had prepared an alternate route in case this happened, so it wasn’t a great disappointment or a major disruption to my plans.

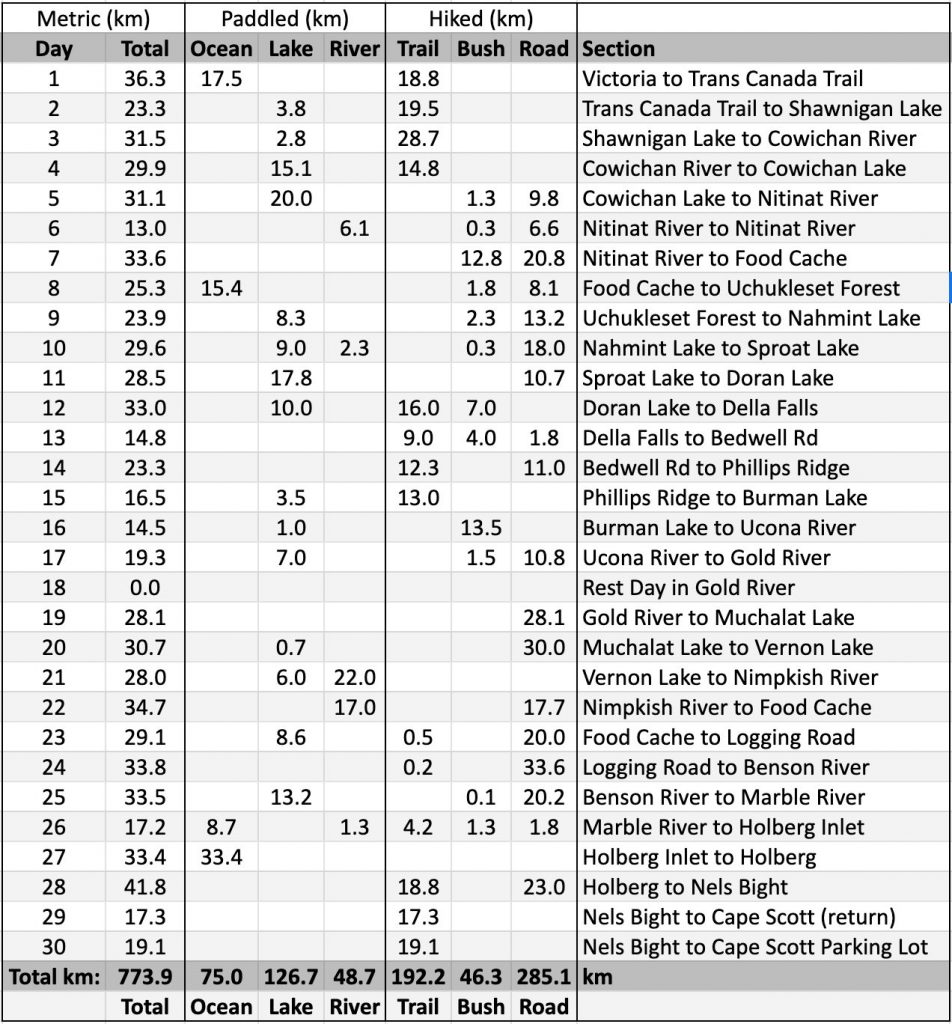

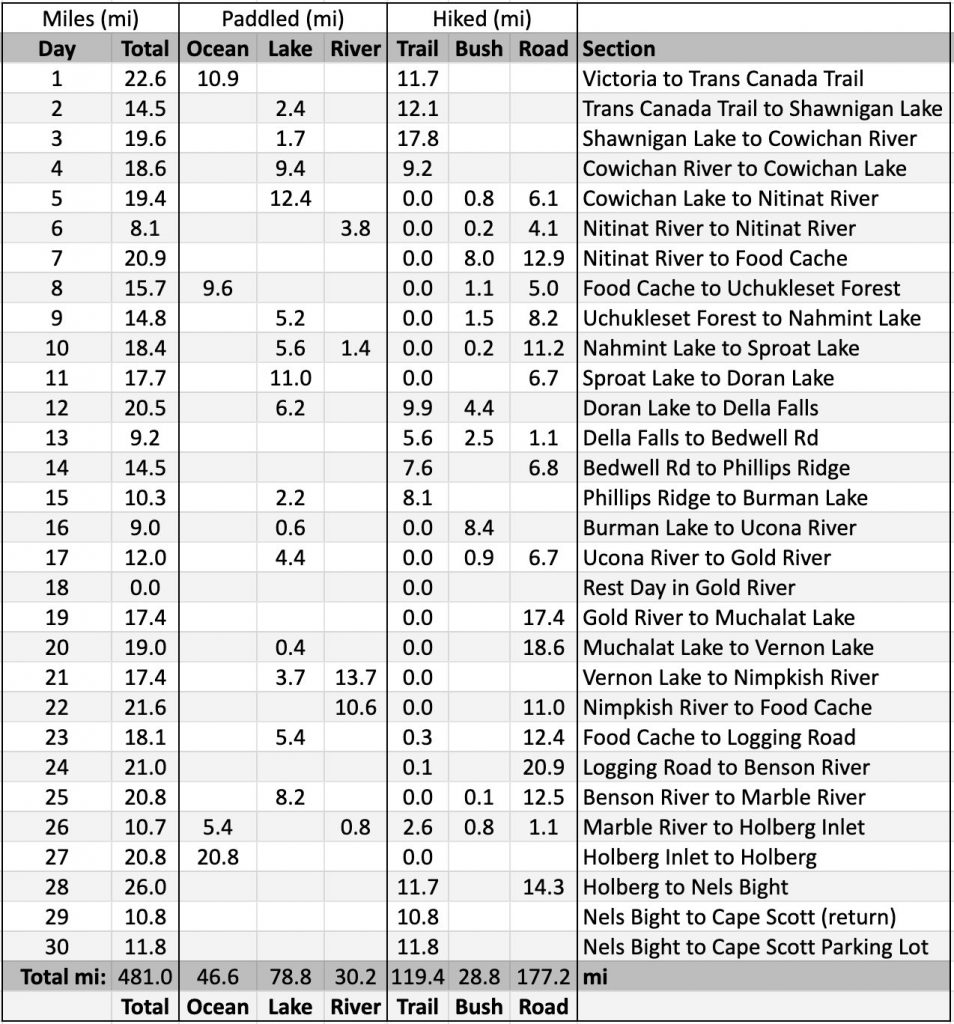

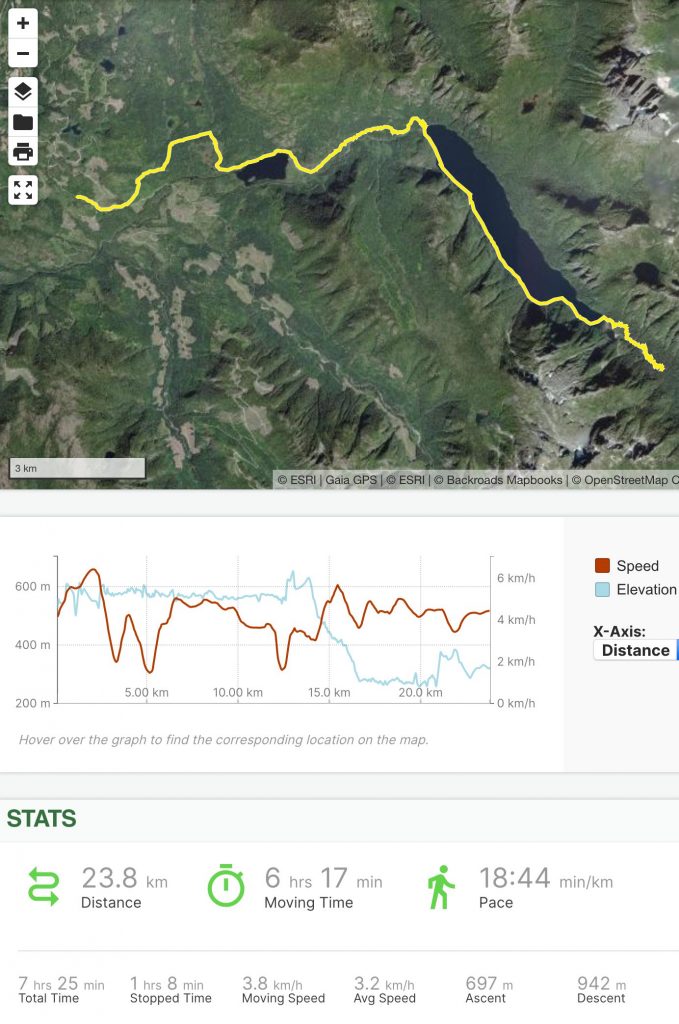

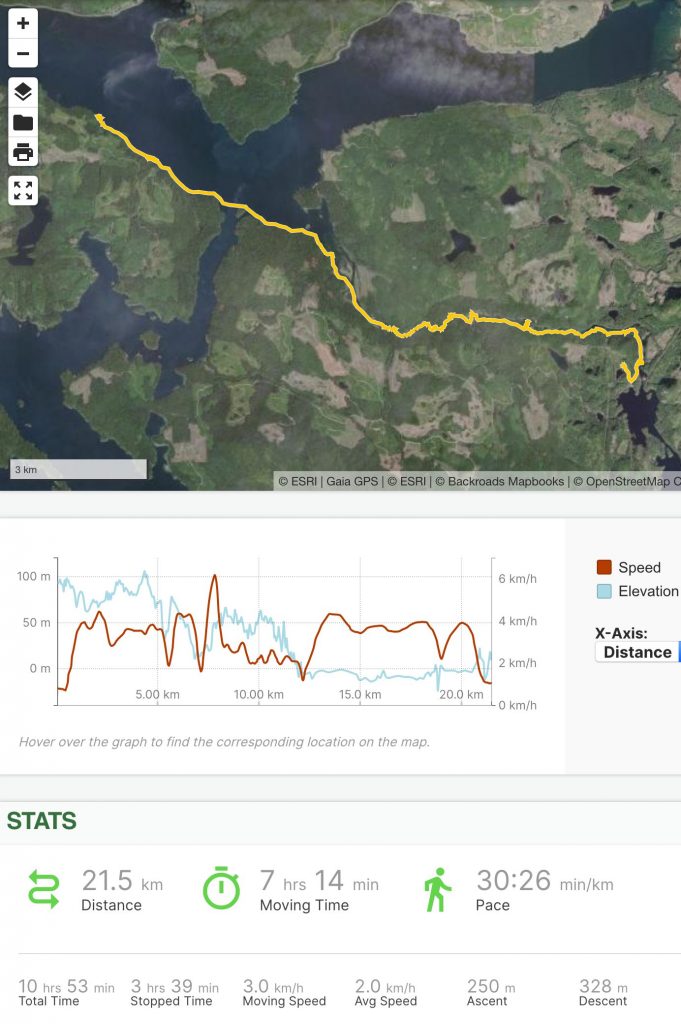

Out of the total 773.9 km (481 miles) I travelled, I paddled 32% (250.4 km, 155.6 miles), and hiked the remaining 68% (523.5 km, 325.3 miles).

Note that some of the distances are approximate; my GPS struggled at times (e.g. in a thick forest at the bottom of a valley during a rain storm). I have substituted map measurements where I think the GPS overestimated the distance I travelled.

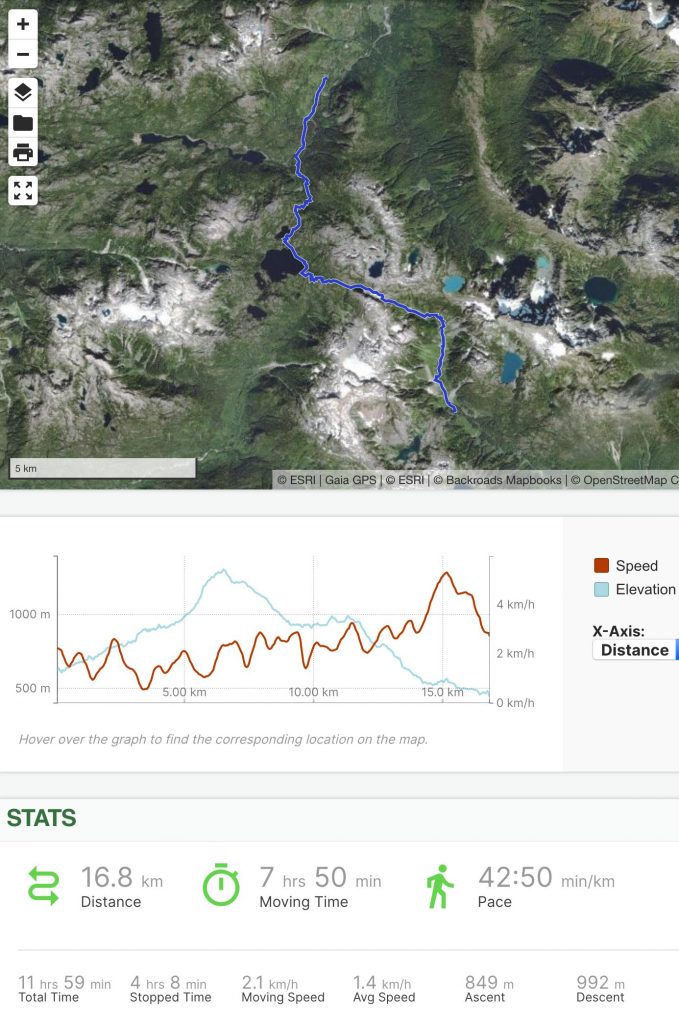

Except for a few relatively short days and one rest day, I was generally hiking and/or paddling for 8-10 hours per day, not including breaks. To a first approximation, you can judge the relative difficulty of each day by how much distance I covered: days when I travelled shorter distances were in more difficult terrain, days when I travelled farther were in easier terrain.

Day 1: Victoria to Malahat

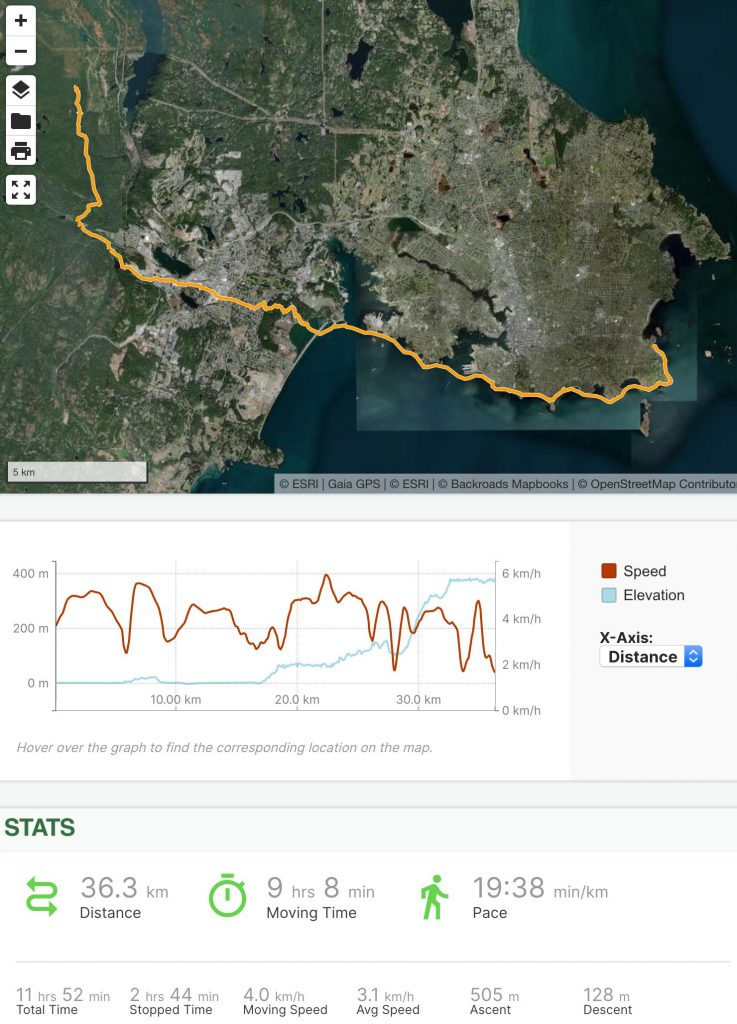

The forecast for August 4, 2020 (Day 1), called for sunshine and westerly winds building to 20 knots in the afternoon, so I got an early start and was on the water before 7:00 a.m.

I said goodbye to Nikki and paddled around Gonzales Point on a falling tide, and then continued west along the city of Victoria’s south shore. For the first hour or so I couldn’t shake the pre-trip jitters – I had spent years planning for this day, and now it had arrived. Had I forgotten something? Did I train hard enough to avoid a trip-ending injury? Would a bear dig up one of my food caches and leave me stranded with nothing to eat? Is a shark about to take a bite out of my packraft?

I’ve always had a mild fear of what lurks out of view beneath the water’s surface, so every submarine hilltop I paddled over gave me a start as it loomed up out of the black depths.

Eventually I found my paddling rhythm and I began to relax and enjoy the beautiful sunny morning. I had been worried about the whirlpools and boils that form between Trial Island and Mcmicking Point, as the current there can reach 8 knots (15 km/h, 9 mph) and many small boats have run into trouble trying to take the shortcut through the passage. I arrived there early and kept close to shore, however, and while there were some noticeable boils and eddies, it wasn’t much different than a large river.

I stopped for a bathroom break at the Ross Bay Cemetery, followed the waterfront footpath to Holland Point, and then inflated my packraft again and paddled along the breakwater and across the mouth of Victoria Harbour, along the Esquimalt waterfront (where a security guard at the Navy base gave me a good hard look), and then crossed the mouth of Esquimalt Harbour to Fort Rodd Hill. I stopped paddling to watch a giant Navy ship steam into the harbour and I was surprised that such a large, fast-moving vessel created a wake no bigger than that of a speedboat. Is some witchcraft being practised to make military ships less visible from above?

I landed at Coburg Peninsula, where I crossed the narrow gravel spit and then paddled across Esquimalt Lagoon to the Royal Roads University boat launch. I stowed my packraft and spent some time admiring Hatley Castle, the campus centerpiece, which has been used as a filming location for many movies and TV shows (e.g. X-Men). I then followed some trails through an old growth Douglas fir forest until I emerged on a busy semi-urban road.

A short walk through the suburb of Colwood brought me to the Glen Lake Trail, which led me to the Trans Canada Trail (a.k.a. The Great Trail). There I began the steep climb up into the Sooke Hills Wilderness Park Reserve, gaining about 400 m (1300′) of elevation. The afternoon was hot and water was scarce along this stretch, so I hiked until I found a small stream, filled all my water containers, and then began looking for a flat place to camp. Several hours had passed since I had seen another person, so I decided to camp just off the trail in a patch of speargrass, which filled my shoes and socks with tiny barbed points.

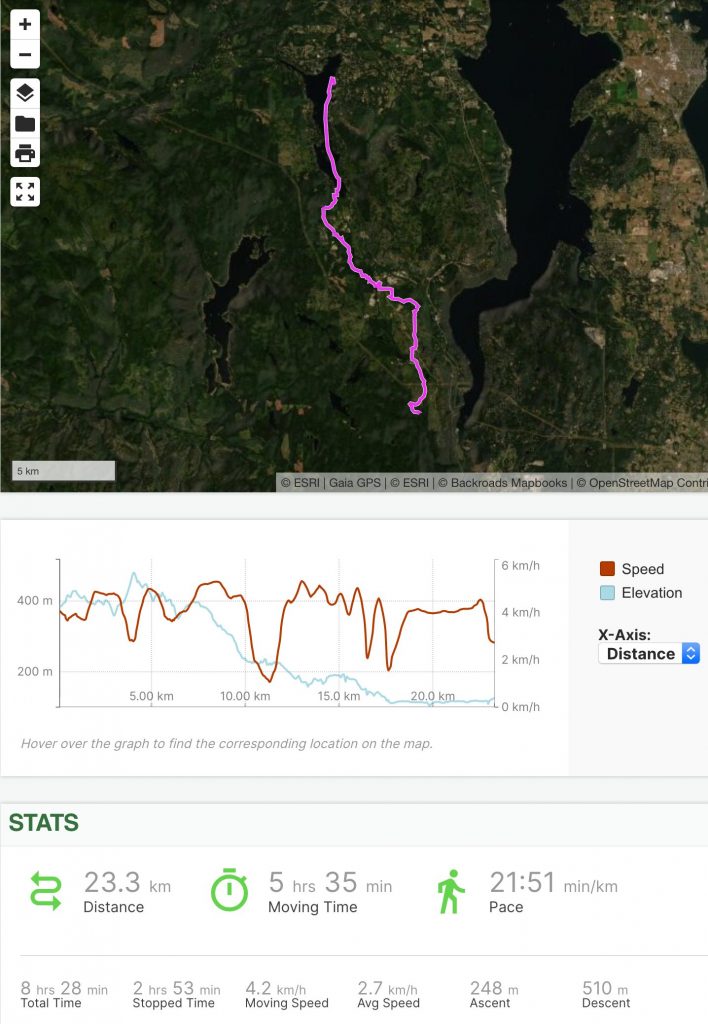

Day 2: Malahat to Shawnigan Lake

Day 2 dawned cool but sunny, with the promise of more heat to come. I packed up my camp and continued north along the Trans Canada Trail, before long reaching a ridge top where I had some views back towards Victoria where I had started the day before. One dog walker and a few hard-core cyclists were the only people I saw on this stretch of the multi-use trail, probably due to its steep grades, which would dissuade casual walkers and cyclists. I did see a mama bear and two cubs though, and I had time to pull out my camera and get a decent video of them.

Finding water proved to be a challenge again, but eventually I came to a bridge over a small stream and I stopped there to filter a couple of liters. Ravens chattered and cawed in the trees above, and at one end of the bridge the Malahat Nation (the indigenous people of the area) had erected a large wood carving of stylized ravens – it was a nice surprise to find such a beautiful piece of public art in that relatively remote location.

Then I began a long descent towards Shawnigan Lake. Near the lake, I left the trail and made my way along a few short roads to a public lake access point on the southwest shore, where I launched my packraft amid a crowd of beached boats.

Shawnigan Lake is only a 45 minute drive from the city of Victoria, and on this sunny summer afternoon the lake was lousy with powerboats. I bobbed along in their wakes, my head on a swivel, trying to avoid being run over as I paddled north into a headwind.

It was only a 5 km paddle to Old Mill Park, where I found a spot to land away from the crowded main beach. My family lives in the area, and my mother, sister, and niece had been tracking my progress via my inReach, and they surprised me at the park. It was still fairly early in the day, but I wanted to visit with them for the night, so we headed to my parents’ house where we ate a delicious home-cooked meal – my last for many days – and I spent the night in a comfortable bed.

Day 3: Shawnigan Lake to Cowichan River

I spent the first couple of hours of Day 3 sorting through the food and supplies I had left at my parents’ house, stocking up for the next several days.

My family then saw me off at Old Mill Park, where I paddled across Shawnigan Lake into a stiff headwind – one of the strongest headwinds I encountered on the whole trip. When I reached the narrow west arm of the lake, the waves were smaller and the wind not so strong, and I was able to paddle to another public lake access point.

These public access points are tiny slivers of land at the ends of roads, and the neighbours do not want people to know they are there, so they’re unsigned and difficult to find without a map and GPS. I wasn’t 100% sure I was in the right spot, but nobody was around, so I landed and sure enough there was a faint trail between two houses leading to a road.

I packed up my packraft and then walked the short distance back to the Trans Canada Trail.

This is a popular section of trail, as it leads to a local point of interest – a giant wooden railway trestle spanning a deep gorge; the 100-year-old Kinsol Trestle is 44 m (144′) high and 188 m (617′) long, making it the largest wooden structure in the Commonwealth. When I was growing up in the area it had been damaged by fire and the ends had been removed so it was difficult to access, and the Keep Off signs made it a fun hangout spot for teenagers. In pursuit of an adrenaline fix, we used to climb the rickety wooden ladders with their rotten and missing rungs, walk across the narrow wooden beams, and rappel down from what remained of the bridge deck.

The trestle has since been restored and incorporated into the Trans Canada Trail, with a proper deck and handrails, so it’s not quite as exciting to cross as it used to be, but it’s much safer now. It must be Instagram famous now too, because there were lots of people walking and cycling to see it on a Thursday morning.

Past the trestle the crowd disappeared and occasionally a cyclist or two would ride past, but for the most part I found myself walking in sunny solitude.

The trail from Shawnigan Lake to Cowichan Lake was built on an old railway grade, so it’s pretty flat and straight. Rural roads cross the trail occasionally, and it passes through forests and farmlands.

I stopped for lunch at a small creek, and then carried on, passing a swampy section where hundreds of tiny frogs had congregated on the trail.

The wind I had battled across Shawnigan Lake had continued through the day, and as evening approached I started thinking about where I might camp for the night. Camping is not permitted in Cowichan River Provincial Park, so my options were limited, and the dense forest beside the trail was riddled with widow-makers – dead trees slowly rotting where they stand, waiting for the right gust of wind to push them over.

I wasted a significant amount of time tromping through the bush, searching for a safe place to camp, and it was dusk before I found a suitable spot just outside the park boundary in a dry side channel of the Cowichan River.

Day 4: Cowichan River to Cowichan Lake

On the morning of Day 4 I packed up and walked for a while along the Cowichan River Footpath. This trail parallels the newer Trans Canada Trail and it’s more scenic, but it’s much slower going because it snakes around in the forest and is somewhat overgrown. Eventually I grew tired of the slow progress, so I left the footpath. Back on the railway grade, my speed increased significantly.

Before long a trio of pickup trucks full of park rangers and trail maintenance crews approached; they stopped to ask where I had come from and I was glad I could truthfully say I hadn’t camped in the park.

My lightweight DIY tripod had broken somewhere along the way, so I stopped to make some repairs at Marie Canyon.

I reached the town of Lake Cowichan around 1:00 p.m. and met up with my mother for a last quick visit. She had driven there to deliver my sun gloves, which I had accidentally left in her car, and she surprised me with a delicious carton of curry, which I devoured.

We said goodbye and I found a trail to the lake shore, inflated my packraft among the driftwood, and started paddling west on Cowichan Lake as the first rainfall of the trip began.

Cowichan Lake is fairly large – over 30 km long and 3 km wide (19 miles long, 2 miles wide). The eastern end is fairly well developed, with houses along much of the shoreline, but travelling west, the shore soon gets too steep to build roads and houses, and there were only a few boats visible in the distance, so it wasn’t long before I felt like I was back in nature, where I belong.

I was a bit concerned about making the 800 meter (1/2 mile) crossing between Bald Mountain and Gordon Bay, as in my experience strong winds can funnel through steep-sided narrows like that, whipping up dangerous waves, but the lake was almost totally calm and when I reached the narrows I paddled across without any trouble.

The shore along this part of the lake is steep and rocky, with cliffs dropping straight into the water, so I kept paddling into the evening until I found a small beach where I could set up my tent, just across the lake from the town of Youbou.

Day 5: Cowichan Lake to Nitinat River

On Day 5 I continued paddling west along the south shore of Cowichan Lake, past the remnants of old logging operations and occasional cottages, small islands, and a few campgrounds.

A headwind picked up in the afternoon, and about 2 km (1.25 miles) from the end of the lake, just as it was getting really difficult to make headway, my packraft’s seat sprang a leak and deflated under me.

The seat was a prototype I had made shortly before starting the trip – a rush job – and apparently I hadn’t welded one of the edges fully and it had slowly peeled apart over time.

I couldn’t keep paddling into a strong headwind without a seat (the lower position makes it much more difficult to paddle efficiently), so I turned for shore and landed on what is probably the worst beach on the lake – there must have been a sawmill there at some time in the past, because in addition to being choked with driftwood, the beach was covered in a thick layer of waterlogged sawdust, which stuck to me and everything else it touched.

I checked my map and saw that there was an old logging road nearby, so I rolled up my packraft and headed into the bush. Unfortunately the road was totally overgrown – it must have been deactivated decades ago, because there were mature trees growing where it had been – so I had a longer bushwhack than I had anticipated, but only about 600 meters, or 1/3 mile. I made it to the South Shore Road without too much difficulty, and I followed the road to the end of the lake, then turned onto another logging road that led me towards the Nitinat River.

As I neared the river, I was again thwarted by densely overgrown logging roads. The bush was quite thick, so I donned my bushwhacking layers (heavy long pants and a button-up long-sleeve shirt) and pushed through it, eventually arriving at the river, where I set up camp on a gravel bar.

I stayed up late repairing the inflatable seat by sewing the edge back together and then covering the stitches with seam sealer. I was so exhausted that I kept making mistakes, looping the thread around the edge of the seat instead of pushing the needle through from alternating sides, but I had to finish it that night in order to allow the seam sealer to dry as I slept, otherwise I wouldn’t have a seat to use on the river the next day.

Finally the repair was done and I passed out in my tent.

Day 6: Nitinat River to Nitinat River

Day 6 was spent attempting to descend the Nitinat River. My packraft’s inflatable seat was holding air again, so I was able to paddle along the deeper pools without any problem, but the water level was quite low and I had to walk through the shallow riffles between the pools.

Before long I reached a canyon, where I used a combination of paddling, lining, wading, and scrambling to work my way downstream past small waterfalls and rapids. Eventually, however, the canyon walls were too steep to scramble and the river too dangerous to paddle, so I retreated up into the forest, where I bushwhacked to the nearest logging road.

I walked on the road for about an hour, and then found a trail back to the river below the canyon. The water level was still low, but the pools between the riffles were deep and long, so I reinflated my packraft and drifted downstream towards Nitinat River Provincial Park.

A few people were camping in the park, so I continued downstream until I found a secluded sand and gravel beach to camp on, right where I had planned to depart the river – perfect. The sand there was covered in elk hoof prints, and as I settled in for the evening, a bear appeared across the river. I spent several minutes watching it amble upstream through the bush until it disappeared from view. A little while later, another bear appeared downstream, but this one began to cross the river towards me so I yelled at it until it changed its mind and walked away.

As I was hanging my food bag before bed (well away from my tent!), I gave myself a good scare when the first branch I tried – a large maple limb – broke and nearly came down on my head.

Day 7: Nitinat River to Bamfield Road

Day 7 started with a short, steep bushwhack up from my riverside campsite to a gravel logging road. I followed the road for a few kilometres to a point where I thought I could bushwhack through the forest to a more direct route, but I could hear heavy machinery working in the forest there, so I continued along the road to my alternate route.

The alternate route was a series of logging roads that – at least on my map – appeared to wind up and around a mountain. The first road was nice, with zero traffic and abundant thimbleberries alongside it, but the next road had deep moats across it every 50 to 100 meters where culverts and bridges had been removed. Those slowed me down, but it was nothing compared to the next road, which was totally overgrown – so much so that I missed the turnoff and kept hiking up the ditched road for a while until I noticed I had gone too far.

I retraced my steps, looking for some sign of a road, and all I could see was a patch of deciduous trees in an otherwise coniferous forest. Sure enough, that’s where the road had been, so it was going to be a bushwhack. I had no idea if the other end of the road was still in use, so I kept my hopes up that I would eventually come to a clear path, but it turned out I had to push through 13 km (8 miles) of bush before I emerged in a recent clearcut with good roads. By that time it was evening and I was parched.

I hurried down the last few kilometers of road towards my food cache, and as I approached the main gravel road that leads to the remote town of Bamfield, a truck drove past, stopped, reversed, and its window rolled down.

“Are you okay?” the driver asked.

I assured him I was fine and we chatted for a few minutes before he drove off towards his home at Pacheena Bay.

“Are you okay?” was probably the most common question I was asked on this trip – or perhaps it was, “Are you lost?” That one always confused me because I couldn’t imagine how any hiker could possibly get so lost as to end up in the middle of nowhere on Vancouver Island. I wonder what thought process leads people to ask that question. I usually avoided telling people what I was doing – if they asked where I was heading I would just name the next landmark, and if they asked where I had come from I would tell them where I started that morning. Unless they kept asking questions I wouldn’t mention the extent of my journey because that almost always ended with them questioning my sanity – I didn’t talk to a lot of people on this trip, but the majority of them used the phrase, “You’re crazy.”

Anyway, after the nice man drove away, I found a small creek, filtered some water, drank deeply, filtered more water, and then checked on my food cache. It was still buried where I had left it, but the hour was getting late, so instead of digging it up I searched for a place to camp. I ended up setting up my tent in a rocky clearcut, where I was surrounded by snorting and bugling elk.

I had hiked almost 33 km (20.5 miles), much of it bushwhacking, and once again I was utterly exhausted.

Day 8: Bamfield Main to Uchuck Creek

On the morning of Day 8, I packed up my camp and then walked the short distance back to where my food cache was buried. I dug it up using my aluminum trowel and then I sorted through the food and supplies.

Because I would be crossing the Alberni Inlet on this leg of the journey and I wanted to do it as safely as possible, I had included my drysuit and foam PFD (life jacket) in this cache along with my food, fuel canister, battery pack, and spare parts. That meant that in addition to several more days’ food, I also had a few pounds of extra gear to carry, but I would be glad to have it just a few hours later.

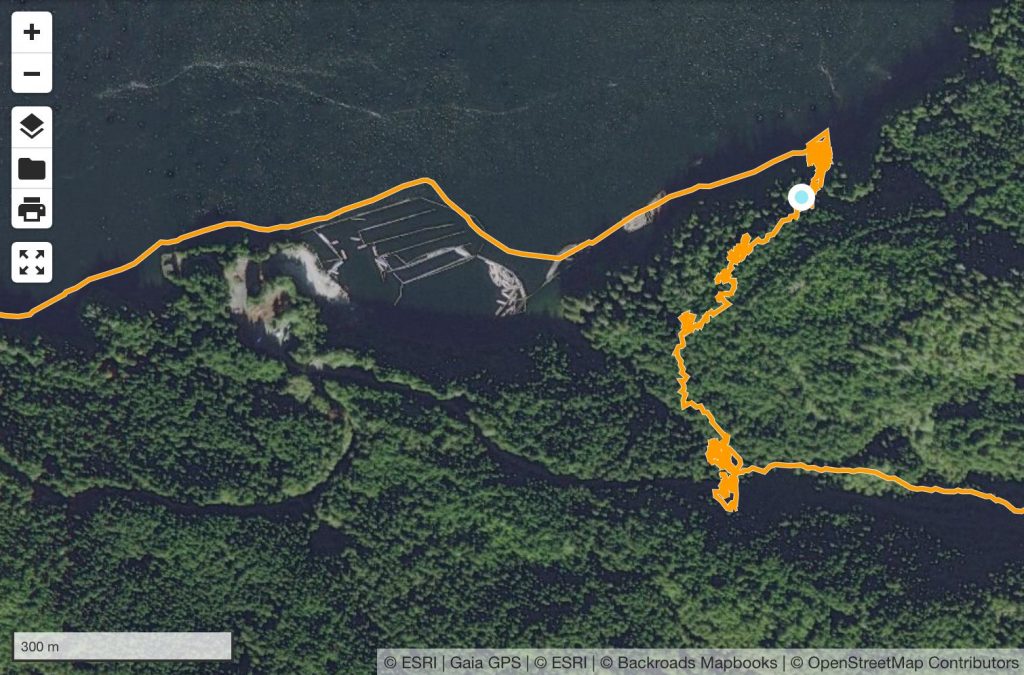

I followed the Spencer Main logging road north towards Alberni Inlet, and waved at a couple of logging truck drivers as they passed. I didn’t see any signs indicating that I should keep out of that area, but the drivers didn’t acknowledge me, which I found odd. Eventually, after following the road for about two and a half hours, I was only 300 m (1/4 mile) from the ocean when I came to a gate and a sign indicating the area was closed to the public. Beyond it, I could hear heavy machinery working; evidently the logging trucks that had passed me were bringing logs to a sorting area beside the water, where presumably the logs were being tied together into rafts so they could be pulled by tugboats to Port Alberni.

Discouraged, I took a moment to examine my maps and ponder my options. The road ahead was the only easy way to access the ocean, but I could not go that way. If I turned around, I would have to walk and paddle for at least four hours to reach a point so close I could almost see it through the trees – that seemed like a big waste of time, so I decided to try bushwhacking around the log sorting area and find my own way down to the water.

I could see from the satellite imagery on my phone that a large area of the water had been enclosed in a log boom, so I knew I had to find a place to launch beyond that. Starting out from the road, the bush wasn’t too thick, but the terrain was quite steep.

I headed east, dropping down into a gully, where I filled my water containers in anticipation of the saltwater paddling ahead, and then I climbed up out of the gully and traversed through the bush along the slope. I knew I was still quite high above the water, yet I could hear waves very close by – that meant there were cliffs ahead. I looked at my topographic map and satellite imagery, trying to determine where the gentlest slope would be. The contour lines were at 20 m (66 feet) intervals, and a lot can change in 20 meters, so they weren’t much help, but I made an educated guess based on the shape of the contours and I pushed on through the bush towards a spot I thought might not be too steep to climb down.

When I say “pushed,” I mean that in the literal sense – the salal bushes and deadfall got very thick and it took me more than two hours to cover the 600 meters (2000 feet) between the road and the water.

Eventually I reached the top of a bluff, where there was a 20 meter drop to the ocean below. I peered over the edge and it looked like I might be able to scramble down if I held onto dead trees that had fallen over the edge and living bushes that grew out of the cracks and level spots. At the bottom, a shelf of rock sloped into the sea, and it looked like it might not be too steep to launch my packraft from there.

Sure enough, I was able to make my way down… until I saw a baby seal in the water below. It was hiding, pressing itself into a cleft in the rock, likely waiting for its mother to return from a fishing trip. I watched it for a while – every few minutes it would come up for air and then, after a few breaths, duck under again to hide.

It was very special to see, but it was kind of a problem for me – the place the seal was hiding in was the place I was aiming for, and I didn’t want to scare it away from the spot where its mother had left it (it’s also illegal to approach marine mammals). I worked my way farther east along the rock ledge I was standing on, looking for an alternative place to launch my packraft, but there was nothing that way except sheer cliffs dropping straight into the water. I returned to my spot above the seal pup, and fortunately for me it had disappeared – perhaps its mother had returned to fetch it – so I descended the final 10 m (30′) to the water.

What ensued next was the most difficult boat launch I have ever experienced. The rock here wasn’t as steep as the cliffs around me, but it certainly wasn’t flat, so I first found a spot that was secure enough to set down my backpack, and then I inflated my packraft, assembled my paddle, and donned my drysuit and PFD. Then I carried everything to the water’s edge, where the waves, while not very large, were big enough to jostle the packraft continuously as I loaded my gear into it while trying to prevent it from grating against the barnacle-covered rocks.

It was a huge relief when I finally had everything loaded and I was able to flop down onto the seat and quickly paddle away from the rocks with my feet still dangling in the water. I took a moment to reposition myself, and then I began paddling west.

As I rounded the first corner, I startled a family of seals resting on a rock only 10 meters (30 feet) away and they quickly flopped into the water and disappeared under the waves.

I was paddling into a fairly stiff headwind and there were whitecaps farther out in the channel, so I stayed close to the cliffs, taking shelter behind every point of land, hoping the overhanging trees were slowing the wind speed at least a little bit. I was surprised to see that the spot where I had launched was really the only feasible option for quite a distance – it had taken a bit of skill and a lot of luck to end up there on my first try, and I shuddered when I realized I could have been scrambling and bushwhacking for many more hours if I hadn’t found it right away.

I was forced to paddle 250 m (1/6 mile) out around the log boom that blocked the waves from entering the log sorting area at the end of the road, and I sighed as I admired the excellent boat launching opportunities there.

After passing the logging operation, I continued west along the south shore of Alberni Inlet for about an hour until I reached the narrowest part of the inlet. By the time I reached Star Point the wind had dropped somewhat and there were no longer any whitecaps in the middle of the channel, so I made a quick decision to cross while the conditions looked okay. I checked my packraft to make sure the air pressure was still good and then turned north and quickly paddled out into the inlet.

The channel is only 800 m (1/2 mile) wide there, so it didn’t take long to get to the other side, but thinking about the things that could go wrong on that particular crossing had kept me up nights. To have it behind me was a great relief… not that I could have landed on the north shore if I had needed to – the cliffs were even higher and steeper there than on the south shore, rising straight out of the water – but just having dry land nearby again was comforting.

The wind picked up soon after I finished the crossing, and once again I couldn’t believe my luck – it had dropped at just the right time and just long enough for me to cross safely. I turned west again and paddled into the wind, not minding it so much now.

I followed the north shore of the inlet for another hour or so, passing a hidden waterfall in a little cove and some interesting limestone formations as I approached Limestone Island. I crossed Limestone Bay, and the wind had really picked up by then. Getting to Brooksby Point was a battle, with whitecaps bearing down on me and confused waters jostling me where the incoming waves interfered with waves reflecting off of the steep shoreline.

I still had about 8 km (5 miles) left to paddle, and I wasn’t sure if the wind would still be in my face after I entered Uchucklesit Inlet. Fortunately the opposite happened – it turned into a glorious tailwind and my speed picked up considerably.

I passed the tiny community of Kildonan, made up mostly of float homes; there’s a floating post office there, and I had considered stopping to send my drysuit and foam PFD home, but by the time I arrived it was 6:30 p.m. and the post office was closed, so I kept paddling. I drew a few curious looks from the locals, who had probably never seen someone paddle by in a packraft before.

The tailwind held strong, blowing me all the way to the village of Hilthatis at the head of Uchucklesit inlet. Before leaving home I had searched online for information about the 1 km (2/3 mile) stretch of land between Uchucklesit Inlet and Henderson Lake, but I couldn’t find any information about access between the lake and ocean. I could see from the satellite imagery that there was a boat launch at the ocean and what looked like a road between the ocean and the lake, so I was optimistic it would be an easy fifteen minute walk between the two. I also saw that the lake was only 5 meters (16 feet) above seal level, so I figured that even if the road wasn’t an option I would be able to paddle and wade up the river to the lake, if necessary.

As I approached the boat launch, a dog started barking and a woman came out of her home to inquire about my intentions. She wasn’t unfriendly, but when I told her I was hoping to get to the lake, either by road or river, she said I needed permission from the local council to pass through their land. She explained that they had had problems with vandalism and people starting fires, and they were putting up signs and security cameras “probably tomorrow”.

I had no way of contacting anyone other than by satellite text message (I hadn’t been near a cellphone tower in days), and even if I could have sent a request, who knows how long it would be before I got a response – days? Weeks? – so crossing the private land (which also encompassed the river) would not be an option.

By this time it was after 7:00 p.m., I had been paddling for nearly five hours, and it would have been impossible to paddle back upwind into the whitecaps, so I waved goodbye to the woman (whose attention had turned to a bear that was now in a standoff with her guard dog) and quickly examined my maps to see where the borders of the private land lay. I headed west along the head of the inlet and landed in a small cove, dragged my packraft onto the rocks, and relieved my aching bladder.

What to do? I could see on my maps some nearby logging roads that might get me closer to the lake without trespassing, but judging from the satellite imagery they would be overgrown. I didn’t have much choice, however, so I packed up my paddling gear and headed into the woods.

I entered a beautiful old coastal forest and almost immediately found a bear’s skull lying on the ground. I had little time to appreciate it, however, because dusk was approaching quickly and this was no place to camp.

I found the logging road, but as I had feared it was completely overgrown, thick with trees and bush. I tried to scramble up the rocky bluffs north of the road but they were too steep and loose to climb safely, so I retreated back to the overgrown road and continued bushwhacking. I pushed on, getting increasingly desperate as darkness was falling and I hadn’t seen a single spot large enough to pitch my tiny tent since reaching land. Finally at around 9:00 p.m., after covering only about one kilometer, I found a place on the old road where, after removing some dead branches from the tightly-packed trees, I could make camp. The ground wasn’t flat, but it would have to do.

I quickly set up my tent in the dark and then found a spot nearby where I could see a small patch of sky through the trees. I waited there for a while as the “Okay” message from my inReach slowly beamed up to a satellite, and then I retreated back to my tent and passed out for the night.

Day 9: Uchuck Creek to Nahmint Lake

The straight-line distance between the place I had camped and the shore of Henderson lake was only 1 km (2/3 mile), but it took me five hours to get there.

I set out at 7:30 a.m. and the entire morning was spent bushwhacking through some of the thickest forests I have ever seen; the salal and salmonberry bushes in particular were so densely intertwined that I was forced to crawl on my hands and knees in places because I could not push through them standing up.

Once I reached the end of the overgrown road, I had to find my own way through the final half-kilometer of steep bluffs to Henderson Lake. The easiest terrain was on private property, so it wasn’t an option; instead, I headed north along the height of land until I could turn east without trespassing. As I approached the lake, I was still high above the water – clearly there were cliffs ahead. I descended as far as I could, hoping I’d be able to find a way down, but only a stone’s throw from the water I realized I was cliffed out.

While leaning over the edge of the cliff, trying to see a way down, I must have stepped on a wasp nest because next thing I knew I was running back up the hill, thrashing through the bush, trying to get away from a swarm of angry wasps. Fortunately my multiple layers of clothing protected me from most of the stings, but I did receive three stings on my ankles.

After retreating from the wasps, I traversed south at a higher elevation until I reached a steep gully that looked like it might lead all the way down to the lake. Sure enough, after scrambling down into the gully it was relatively easy to reach the lake.

Across the water I could see the mouth of the river and the end of the road I had hoped would be a fifteen minute walk from the ocean. Instead, I had taken a seven-hour detour through some of the most difficult terrain I encountered on the entire trip, but it was finished now.

I inflated my packraft in the bush at the water’s edge, loaded up my gear, and paddled out into the lake. I crossed over to the eastern shore and as I began paddling north, a light tailwind helped me along.

Aside from the breeze, Henderson Lake was eerily quiet, with no signs of life other than the plants and trees surrounding it. The crescent-shaped lake is about 20 km (12 miles) long and beautifully deep and clear, but I didn’t see a single boat or any indication that humans had ever been there. I had been paddling for an hour when I saw the first bird, a gull that had strayed inland from the coast. Perhaps the animals are afraid of the Thunderbird that nests in the mountains west of the lake, in Thunderbird’s Nest (T’iitsk’in Paawats) Protected Area – I certainly felt the power of the place and I was honoured to see it, even from a distance.

In spite of its reputation as the wettest place in North America, the sun was shining as I paddled towards the midpoint of Henderson Lake, where a small camping area is designated on a creek delta. The tailwind was growing stronger and stronger as I paddled, and by the time I arrived at the deserted campsite, I was glad to be leaving the whitecapped waves behind.

I spent an hour and a half at the campsite, drying all my clothes and gear in the sun and wind, enjoying the beautiful solitude among some giant cedar trees (the third-largest known Western red cedar tree in Canada lives at the far end of the lake).

After I packed up my gear, I headed up the campsite’s short access road and there I realized I was on the wrong side of a locked gate – oops! A sign affixed to the gate said the campsite was closed for the fire season, and as I walked around the gate I could smell the fresh yellow paint still drying.

I hustled up to the main logging road and then turned onto the connector road that climbs up and over the pass between Henderson Lake and Nahmint Lake. A couple in a minivan passed me on the road – the only people I saw all day. They stopped to ask if I was okay and I gave them a thumbs up – it was odd to encounter people in a vehicle like that in such a remote place.

I climbed about 350 vertical meters (1150′) up the steep gravel road, and then descended again to Nahmint Lake. There I set up camp in a clearcut at the end of a logging spur and settled in for the night. There were lots of signs of bear activity in the area, but the surrounding trees were gigantic, their lowest branches probably a hundred feet off the ground, so there was nowhere to hang my food and I ended up sleeping with my food bag in my tent.

Day 10: Nahmint Lake to Sproat Lake

From my campsite to the southwest shore of Nahmint Lake, it was a short walk through a clearcut full of giant stumps, charred logging slash, and fireweed. When I reached the rocky beach, I inflated my packraft and started paddling north on the glassy lake. The water was so clear and flat that I could see quite far down, and I watched as orange-bellied newts (salamander-like amphibians) swam up to the surface for air and then swam back down to the bottom.

The lake is about 9 km (5.5 miles) long and accessible by logging road, but I had it entirely to myself, and I consider it to be one of the most enjoyable paddling experiences I had on this trip. The shore was steep in most places, but I did pass some beautiful beaches, including a Recreation Site with a cabin and outhouse.

At the north end of the lake, I passed one tent and I saw a pickup truck off in the distance across the lake, but I didn’t see any people.

From the north end of the lake, I paddled and waded about 2 km upstream on the Nahmint River to a beautiful little canyon with deep, clear green water, and from there I followed the steep logging roads up past Gracie Lake and then down again into the Sproat Lake drainage.

To reach my next food cache I would have to cross Taylor Arm, the western limb of Sproat Lake (a 1.4 km / 1 mile crossing), and before I reached the lake the road forked and I had to make a decision about which direction to go. Either road would lead me to the lake, but one would take me west of my cache, the other would take me east. If there was any wind on the water, I wanted to make the crossing on a down-wind trajectory, but at the fork in the road I couldn’t tell which way the wind would be blowing, so it was a gamble. Coming down from Gracie Lake, the wind had been at my back (a south wind), but as I neared Two Rivers Arm (the southern part of Sproat Lake) the wind on the lake appeared to be coming from the east. I’m not sure why, but some intuition told me that the wind on Taylor Arm might be blowing in the opposite direction, so I took the left fork and headed west.

Sure enough, when I eventually reached a point where I could look down on Taylor Arm, the waves were coming from the west. I had made the right choice, but unfortunately the wind was blowing so hard that crossing the lake wouldn’t be safe. Instead, I continued walking west along the gravel road, thinking maybe the wind would die down by the time I found a convenient way to access the water. (The terrain between the road and the water was very steep and I didn’t want a repeat of my Henderson Lake bushwhacking+cliffs experience.)

Eventually I found a way down to the water, but by this time it was late in the evening, so I made camp in a beautiful lakeside forest, complete with large bear tracks leading right past my tent.

Day 11: Sproat Lake to Doran Lake

By morning, the wind on Sproat Lake had died down and I was able to cross without difficulty. When I reached the north shore, I backtracked east to Taylor Arm Provincial Park, where I landed, rolled up my packraft, and walked a couple of kilometres to my second buried food cache.

I spent an hour or two digging up the cache, sorting through supplies, and reburying unneeded items to be retrieved later, and then I walked back to the lake, inflated my packraft, and paddled west. It was a beautiful sunny day, and as morning turned into afternoon, a tailwind picked up and helped me along.

A two-lane highway leading to Tofino (a popular tourist destination) runs parallel to the north shore of Sproat Lake, so the lake is a popular drive-in camping destination. On this sunny summer Friday, all of the places where I had thought I might transition from paddling to hiking were occupied by campers. I also found it difficult to tell from the water what was public land and what was private property (there are houses and cottages in some areas along the shore), so as I neared the end of the lake I kept looking for an appropriate place to land, but I wasn’t having any luck. Eventually I reached the end of the lake and I still hadn’t found an appropriate spot, so I looked at my maps and saw that if I paddled a little way up the Taylor River I would reach a bend in the river close to the highway, and I figured I could land there. Unfortunately I didn’t check the satellite imagery, and instead of paddling into the river’s mouth, I accidentally paddled into a marshy channel that eventually petered out into a muddy swamp. This wouldn’t have been a problem if the tailwind had been light – in that case I would have just backtracked – but by this time it was blowing quite hard and I wanted to avoid paddling back upwind if I could.

I nosed my packraft through a gap in the reeds and managed to climb out onto the soft, floating moss without sinking in too far. I explored a little bit in either direction and it appeared I would be able to walk to the road without wading through too much swamp, so I packed up my paddling gear and made my way back along the soggy shore until I reached a spot where full-sized trees grew between the water and the road. I figured that the ground under the trees must be reasonably solid, so I bushwhacked toward the them, avoiding the mud as much as possible.

Under the trees the ground was muddy but solid, and from there it was a short distance to a gravel access road. I reached the road and began walking west, sweating profusely – now that I was out of the wind, the heat was oppressive, and I had neglected to fill my water containers before entering the swamp.

I carried on and soon reached the place I had been trying to paddle to, a bend in the Taylor River where it passes close to the road. I stopped there to filter water and cover myself in sunscreen, and then I crossed the highway and began the 700 m (2300′) climb up to Doran Lake.

The gravel road to Doran Lake is a series of switchbacks up a steep mountainside, and even though it’s right off of a well-travelled highway, I didn’t see a single person or vehicle there.

Aside from the heat, it was an enjoyable climb – I had been afraid I would be totally exposed to the sun, so I was pleasantly surprised to find myself in the shade most of the time, first under big leaf maple trees low in the valley, then under hemlock trees higher up, and finally under silver-barked cedar trees near the top of the ridge. When there was a break in the trees I had views across Sproat Lake to Klitsa Peak and Brigade Mountain.

I was cruising along near the top of the climb when I heard something rustling in the bushes beside the road up ahead. For some reason I assumed it was a deer, so I didn’t make any noise and just kept walking. As I passed the spot where the rustling was coming from, I looked to my left and locked eyes with a black bear less than 10 meters (30 feet) away.

“Hello!” I said, and hurried on, looking back over my shoulder. Fortunately the bear wasn’t interested in a confrontation and it let me go on my way.

Given the number of people camping at Sproat Lake below and the fairly easy road access from there, I had expected to find at least a few people camped at Doran Lake, but when I reached the lake in the evening I was surprised to find that I had it all to myself. It was a lovely little lake, about a kilometer and a half (one mile) long; unfortunately the previous occupants of the informal campsite had left some fish carcasses behind, so there were plenty of wasps about, and I quickly decided it would be a good idea to find a different place to camp. By this time the sun was setting and dusk wasn’t far off, so I quickly inflated my packraft and paddled the length of the lake.

The shores of the lake were rocky and sloped fairly steeply from thick forest into the water, so I didn’t find a great campsite, but there was one rocky spot that had been somewhat levelled by previous campers, and I did my best to set up camp there without making holes in the bottom of my tent.

As the sun went down the wind disappeared, and I set up my camera to capture a timelapse of the beautiful rosy alpenglow and the mirror-like reflection of Klitsa Peak on the lake. Sadly, due to user error, this spectacle was only captured in my memory.

Day 12: Doran Lake to Della Falls

As I emerged from my tent in the morning and looked around, I realized there were about twenty standing dead trees within striking distance of my tent – oops! I had been so focused on finding a flat spot the evening before, I had forgotten to worry about “danger trees”. Oh well – all’s well that ends well.

I packed up my gear and donned my bushwhacking layers before heading into the forest north of Doran Lake. I was aiming for a logging road only a kilometer away, and I was soon soaked from the dew-covered bush and swampy ground. The terrain was steeper and more difficult than I had anticipated, but eventually I reached the road, which appeared to have been abandoned about ten years before, judging from the size of the trees growing out of it.

This network of gravel logging roads is not connected to any other roads – it only leads down to the shore of Great Central Lake 600 vertical meters (2000 feet) below. Presumably road-building machines were carried across the lake on barges, and then the area was logged and the trees were removed the same way. Now the roads are abandoned and they are quickly becoming overgrown – I might have been the first person to walk down them since logging operations ceased (I have never heard of anyone else hiking in this area and I didn’t see any signs of recent human activity). I was somewhat annoyed to be bushwhacking yet again on what I had thought would be an easy road walk, but eventually I arrived at the lake.

Great Central Lake is about 30 km (20 miles) long and only 2 km (1.6 miles) wide, with an east-west orientation that makes it notoriously windy. The last time I had been there was on a canoeing and hiking trip with three friends in 2002, and because of the strong westerly wind, what had taken us a day and a half to paddle in one direction had then taken us only four hours to paddle back.

When I reached the shore the wind was blowing strongly from the east and I needed to go west, so I didn’t waste any time getting out onto the water to take advantage of the tailwind.

Unlike Sproat Lake in the next valley over, Great Central Lake is not well travelled; I did see a few powerboats in the distance, but for the most part I had the huge lake to myself. I made good time paddling downwind, mostly staying close to the south shore, but I cut across the larger bays and near the west end of the lake I made a long diagonal crossing to the north shore, keeping the wind mostly at my back.

At the west end of Great Central Lake is the Della Falls trailhead. The trailhead is only accessible via the lake, and being a sunny summer weekend, there were several canoes and kayaks stashed there when I arrived, and as I packed up my paddling gear two more canoes arrived.

By this time it was already mid-afternoon and I was still 16 km (10 miles) from the Della Falls campsite, where I planned to spend the night, so I hurried on. After all of the bushwhacking I had been doing, it was nice to walk on a (mostly) maintained trail for a change, and I made good time.

I briefly considered staying at the first camping area beside Drinkwater Creek, but a cold and humid wind was blowing there, so it didn’t feel very inviting, and the campsite there was completely empty so I figured there would be plenty of empty spots at the main camping area a couple of kilometers ahead. When I arrived there, however, the campsite was packed – I had forgotten about the water taxi service that delivers hikers to the trailhead, so the small number of boats I had seen there did not represent the number of hikers visiting the falls on this sunny weekend.

By this time, dusk was falling and I was desperate to find a place to set up camp. I roamed the campsite and the surrounding forest, looking for any unoccupied flat spot and asking everyone I encountered if they had seen an empty spot, and each group directed me a little farther up the trail.

Near the falls I met a solo hiker coming in the opposite direction and we chatted for a few minutes. It turned out he had come down the steep bushwhacking route I was planning to go up the next day, so I asked him about his experience and I wasn’t encouraged by his responses – when I asked him if he thought he could get back up the way he had come, he thought about it for a long moment and then said, “Maybe without a pack.”

I didn’t have time to dwell on that discouraging answer – I needed to find a place to sleep – so we said goodbye and went our separate ways.

Finally I found an acceptable tent spot in a dry creek bed beyond the falls. I quickly set up camp there and then hurried to the base of Della Falls – the tallest waterfall in North America at 440 m (1440 feet) – where I filled my water containers while trying to avoid getting myself soaked. The falls were unimpressive from this vantage point at this dry time of year, but the spray was enough to dampen my clothing right before bed.

I cooked dinner in the dark and then stashed my food bag in one of the bear-proof bins provided by BC Parks, and then I crawled into my tent. It was odd to be camping at an actual campsite – a first for this trip. I was well away from other people on my rocky creek bed, but the forest was littered with toilet paper blooms and the smell of wood smoke from illegal camp fires hung in the air.

Day 13: Della Falls to Jim Mitchell Lake Road

After a decent night’s rest I packed up and left the Della Falls campsite behind.

There is no trail beyond the falls, just a narrow, cliff-lined valley littered with talus and thick bush. One guidebook marks part of the valley as “Extremely Difficult,” but doesn’t explain what that means, and in spite of extensive searching online, I couldn’t find much useful information about the area.

The guy I had met the night before had descended this way and he said it was steep and very bushy – he described clinging to alder and cedar branches to lower himself down the cliffy waterfall section ahead – and when I asked him if he thought he could hike back up that way he wasn’t sure. Because of the heavy snow loads here in winter, all of the branches point downhill, so bushwhacking uphill would be going against the grain. I had to try it though, because the only other option would be to backtrack and scramble up and over a rather large mountain.

Nervous about the terrain ahead, I followed the Drinkwater Creek upwards, scrambling over and between chair- to house-size boulders, avoiding the bush wherever possible. I made slow progress north, and when the valley began to turn west I kept to the eastern slope, gaining elevation where I could, trying to avoid the steepest areas. I knew there were waterfalls ahead, so I stayed away from the creek, hoping I could avoid any cliffs.

For the most part this worked, but I couldn’t avoid the bush, which was extremely thick. Slide alders, gnarled cedars, devil’s club, and huckleberries covered the boulder talus, making progress slow and somewhat dangerous – it’s difficult to travel safely over jagged boulders when you can’t see your feet. There were also lots of signs of bears in the area; the guy I had met the night before said he saw several of them on his way down, but I was climbing up, facing the slope, so I didn’t see any (ignorance is bliss).

I could hear the waterfall(s) off to my left, and by waiting until the sound seemed to be coming from below me before turning back towards the stream, I managed to keep away from any sheer cliffs. I was sweating profusely under a blazing sun, wearing multiple layers to protect myself from the thorny bush, but my gardening gloves were no match for the devil’s club and I would be picking spines out of my hands for days to come.

Eventually the bush thinned and I was past the worst of it. There was still a long climb to the Drinkwater/Bedwell pass ahead (700 vertical meters or 2300 feet above my camp site), but I knew I was going to make it, so the loose boulders didn’t seem so bad.

I reached the top of the pass at 3:20 p.m., nearly seven hours after I had left camp in the morning.

I sat down at the edge of Little Jim Lake and filtered water in a daze. I had just overcome one of the biggest unknowns of the entire trip, but instead of feeling great about my accomplishment, all I could think about was what this could mean for the days ahead. If I followed my intended route through central Strathcona Park, bushwhacking from Burman Lake to Gold River via the Ucona River valley, I would be venturing into a much more remote area where as far as I knew no one had ever attempted to hike before. If the bush was as bad as what I had just come through (or worse!) I might spend days there trying to find a way through. It had taken me nearly seven hours to cover the four kilometers (2.5 miles) between Della Falls and Drinkwater Pass and I was now totally exhausted – and that was in good weather. The route to Gold River included ten times as much bushwhacking as I had just done, and who knew what the weather would be like a few days hence in this notoriously rainy part of the world.

As I followed the trail down towards Bedwell Lake, a feeling of dread began to overcome me and I started considering alternate routes through Strathcona Park. I could easily change my plans to bypass the central mountains and instead paddle north up Buttle Lake, west on Upper Campbell Lake, and then walk to the town of Gold River via Highway 28. This would be much, much easier than crossing through the heart of the mountains, and the more I thought about it, the better I liked that idea.

Either way, I had to first reach the Phillips Ridge trailhead to retrieve my food cache, and given how long it had taken me to reach the pass, I would not have time to get there today. I decided I would sleep on the big decision and see how I felt in the morning.

I hiked down past Bedwell Lake and briefly considered camping at Baby Bedwell Lake, but it wasn’t even 6:00 p.m. yet, so I kept going, figuring I could camp at the trailhead if necessary.

I ran out of water on my way down the Bedwell Lake Trail, and I foolishly passed by a couple of streams without filling my water containers because I figured there would be more streams ahead and they would be easier to access. This turned out to be a bad assumption, and I reached the trailhead without any water. I could have backtracked to fetch water, but I stubbornly wanted to keep moving forward and I saw on my map that there were several streams crossing the road ahead, so I kept walking.

There were indeed streams crossing under the road, but some of them were dry and others were inaccessible. I had never seen anything like it before – small streams cascading down cliffs into deep pits on the uphill side of the road, where they disappeared into some sort of culvert (presumably), and there was no sign of water on the downhill side of the road. The water-filled pits were fenced off, but even if there weren’t fences around them, I wouldn’t have tried to access them – the walls were just too steep.

I kept walking down the gravel road until finally I reached a stream that was somewhat accessible. I filled my water containers there at around 8:00 p.m. and then walked until I reached a widening in the road where I could set up my tent without fear of being run over – the forest on either side of the road was extremely steep (no place to camp there) and I was so tired I was willing to sleep on an active road.

Only one vehicle drove past as I set up my tent, cooked dinner, and got ready to sleep at the edge of the road. Another one or two vehicles drove by in the night, but I was too tired to care.

Day 14: Jim Mitchell Lake Road to Phillips Ridge

On the morning of Day 14, I woke up feeling much better than I had felt the night before, and my desire to take an easier route around the mountains had waned.

As I walked past the foot of Buttle Lake I could see a strong wind was creating whitecaps from the south – I would have had a tremendous tailwind if I had decided to go that way – but I left the lake behind and walked the road through Myra Falls mine.

The underground mine at Myra Falls is an anomaly – an active mine in the middle of a wilderness park. Mining there for copper, zinc, and lead was approved in the 1960s and it has continued ever since. To reach the trailhead, I had to walk through the busy mine site. I checked in at the security booth and the guard there had to call her supervisor on the radio to ask what to do with me, as she had never had a hiker ask to walk through the mine before (normal people drive to the trailhead). She asked if I happened to have a high-visibility vest I could wear while passing through, and I just laughed.

Past the mine, I headed into the forest to retrieve my food cache. I stocked up with plenty of food because I wasn’t sure how many days it would take to reach Gold River, and it was noon by the time I had sorted through all of my food and supplies and then re-buried the cache. I didn’t have much water left and I was about to start a 1200 meter (4000 foot) climb, but I looked at my map and saw a few streams crossing the trail above, so I decided to take a gamble and hope that water was flowing there instead of going in search of water in the valley bottom.

I began hiking up the many switchbacks of the Phillips Ridge/Arnica Lake Trail, which climbs through a lovely old growth forest. Fortunately my gamble paid off and there were a few spots where water was accessible within a few hundred meters of the trail, so I didn’t go thirsty for long.

I only passed one other group on the trail – an older couple who were on their way down from a day hike to Arnica Lake.

I reached the lake at around 3:00 p.m. and I carried on up towards the ridge top. I passed a couple of young women who had just climbed the Golden Hinde (the island’s tallest mountain) and they said there was almost no water on the ridge ahead, so after I said goodbye to them I stopped to filter water at the next tarn. Shorty after that I passed another couple who said there was plenty of water ahead; I figured the truth was somewhere in the middle, but to be on the safe side I continued carrying the 3.5 litres I had filtered – extra weight for the last 250 vertical meters (800 feet), in addition to my already heavy pack containing food for up to six days.

When I reached the crest of the ridge, the views were spectacular in all directions. By this time it was 5:00 p.m. and I wanted to set up camp relatively early, so I continued hiking for another hour and a half before finding a place to camp. I spent quite a while searching for the perfect tent spot and my efforts paid off – I found a relatively flat spot that was protected from the wind, near a small tarn, with great views all around. Of all the places I camped on this trip, this one was probably my favorite. As I readied myself for bed, I watched as the sun set and clouds from the Pacific spilled over the ridges to the west and filled the valleys below.

Day 15: Phillips Ridge to Burman Lake

On Day 15 I woke to a spectacularly fiery alpine sunrise. I followed Phillips Ridge west and passed a couple of hikers camped near a large tarn.

The sun was shining but I could see clouds moving in from the west, so I made the best of the morning, soaking in the views and capturing lots of video clips.

Phillips Ridge is well-travelled, being the easiest way to access the Golden Hinde (relative to the other routes, that is – it’s still a very strenuous hike!), and there were plenty of cairns to mark the way, so route-finding wasn’t difficult.

Where the ridge turned north, broken clouds filled the valley to the west and flowed in wisps over and around me. There were one or two short scrambly descents – probably Class 3 – that caused me to back up carefully and put away my camera before proceeding using both hands for stability, but overall the route was less frightening than I had expected.

I passed two more hikers on the ridge and when I looked back some time later I saw them through the clouds, descending a steep section I had passed earlier, looking tiny on the mountainside and giving scale to the vast mountain landscape.

At a low point in the ridge I stopped to put on my bushwhacking layers once again and then I descended the steep trail that leads to Carter Lake. I had read about this route and was feeling apprehensive about the steepness of the descent – it had been described as very steep and bushy, and being somewhat afraid of heights I wasn’t sure how I would feel down-climbing there all alone. I needn’t have worried, however – it was fairly steep, requiring the use of one hand for stability in some places, but it was just a trail – nothing like the frightening scramble I had imagined.

When I reached Carter Lake I came upon a group of four hikers, one of whom was injured, possibly very badly. They had just descended the same trail I had come down and one of them had accidentally dislodged a large rock, sending it tumbling down the hillside. She just had time to yell “Rock!” before it struck her friend’s backside, sending the woman flying through the air like a rag doll. Together, the three other companions had helped the woman to the lake, and now she lay there on a camping mattress, unsure of how injured she was and whether or not she would be able to hike out.

I offered the use of my inReach’s S.O.S. function, but they had their own satellite communicator and, as it turned out, two of their party were Search and Rescue volunteers and they had all taken Wilderness First Aid courses, so they were well-equipped to assess her injuries and handle the emergency without my help. The woman was in good spirits, so I chatted with them for a while before carrying on my way, and after I returned home I followed up with them and learned that she had been able to limp back to the trailhead over the next few days – scary stuff, but a good outcome.

I walked the trail past Carter Lake and on to Schjelderup Lake, where I inflated my packraft and paddled easily on the strikingly clear azure water past the notorious boulder slope that drives hikers crazy as they attempt to hike around the lake.

At the north end of Schjelderup Lake, I stowed my packraft again and began the 250 meter (800 foot) climb up to Burman Ridge. I was a bit apprehensive about this route, as the terrain looked pretty steep on my topo map and I wasn’t sure how much fall exposure there would be, but it turned out to be fine in summer conditions (in snow and ice it might have been a different story).

When I reached the crest of Burman Ridge, I began the 350 meter (1150 foot) descent to Burman Lake. The ridge is broad and bluffy, and the well-cairned route winds down from open alpine to steep coniferous forest, through large steps of granitic rock.

Throughout the day I had had views of the Golden Hinde, the tallest mountain on Vancouver Island, and now I was approaching the bottom of the most commonly used route up. I had climbed it with the Alpine Club in 2006, and even if the mountain hadn’t been shrouded in cloud as I approached it now I wouldn’t have attempted the climb again on this trip. Even the easiest route up is a class 4 scramble requiring significant route-finding skills; in 2006 we had climbed it unroped, but on the descent we took a different route and ended up needing our rope on a couple of exposed sections. I wasn’t about to attempt something like that alone and risk jeopardizing the larger goal of this trip.

At the foot of the Golden Hinde I walked a short distance along a muddy cleft in the rock to Burman Lake. The shore was choked with driftwood so I balanced on a log while I inflated my packraft and then I set out to paddle across the lake.

By this time it was 6:30 p.m. and a headwind was blowing from the west, the clouds had closed in around the lake, and the park felt much less inviting than it had that morning up on sunny Phillips Ridge. I crossed the lake and landed near the outlet, where I spent some time looking for a flat spot to camp. At around 7:00 p.m. I found a place near the lake where a game trail came close to the shoreline and there were many signs of recent bear activity. I couldn’t find any other flat spots so I set up my tent there. As the fog rolled in and it began to rain, I settled in to sleep, trying not to worry about the weather and the long bushwhack through unknown terrain ahead.

Day 16: Burman Lake to Ucona River

I woke up to rain on Day 16, packed up my gear, and prepared myself to get wet. From the western end of Burman Lake I hiked west-northwest across the slope below the shoulder of the Behinde, the mountain just west of the Golden Hinde. The forest was a mix of large old-growth trees and an understorey of soaking wet berry bushes.

I crossed a couple of steep-walled gullies, and I had to lower myself into them and climb back up by holding on to berry bushes and slide alders, but overall the terrain there wasn’t too steep. I had brought a 20 meter haul rope that I was prepared to use to lower myself or raise my backpack if needed, but so far I was doing okay with just the “green belays”.

After about an hour and a half, the terrain levelled out and I passed a couple of ponds where I saw a boot print in the mud – the last sign of humanity I would see that day. From there, most people would head north to join the Elk River Trail, but I headed west towards some unnamed lakes where, as far as I could tell from my research online and in books and maps, no one else has ventured.

Beyond the ponds, the terrain got steeper, with stair step-like bluffs covered in moss and trees. Route-finding was a challenge, and the bluffs forced me to cross and re-cross a stream several times in search of a path, but when in doubt I followed elk trails and even when I got cliffed out they always led me out of trouble.

By the time I reached the first unnamed lake it was 1:00 p.m. and in spite of my rain gear I was soaked to the skin and cold enough that I needed to keep moving to avoid hypothermia. The terrain around the lake was rocky and steep in places, so I quickly inflated my packraft, paddled the one kilometer to its western end, and then stowed my packraft again before heading back into the bush.

From the lake’s outlet, I contoured west around the lower slope of an unnamed mountain for about 500 meters (1500 feet), and then I began climbing up towards the pass at the headwaters of the Ucona River. The slope was soggy, but not too steep, and near the top I found a game trail to follow up.

I celebrated briefly at the pass – another obstacle overcome – before hiking north past a small unnamed lake (or large pond) and then attempting to follow the river. Large boulders from the steep slopes above made the going difficult, so I paid close attention to the animal trails and followed them whenever I could.

Below a series of ponds, the terrain got steep again. The contour interval on my maps was 20 meters (66 feet), so the cliffs, which were between five and twenty meters tall (15-66 feet), didn’t appear on my maps. I followed more elk trails between the cliffs, realizing that even with my satellite imagery and topo maps I wouldn’t be able to improve on the routes that they had honed over countless generations. Elk aren’t bothered by mud and stream crossings, however, so my feet were repeatedly soaked in cold water as I waded back and forth across the stream.

Even following the elk trails was difficult and slow-going. The bush was thick, the rain kept falling, and I climbed over and under countless fallen logs. I had to keep moving to stay warm, and after a while I realized it had been hours since I had seen a spot flat enough to pitch a tent.

I was at the bottom of a steep-sided valley in a forest that grew on a bed of boulder talus. The stream bed I was following was full of boulders, and the rare gravel bars I came across were only inches above the water line; with all the rain that had been falling, I wasn’t about to try to sleep on one of those.

My goal for the day had been to reach Donner Lake, and I had travelled as fast as I could, but the terrain was too difficult and by 7:00 p.m., after ten and a half hours of hard travel, I had only covered about twelve kilometers (7.5 miles). I realized that at this rate I would not reach the lake before dark, so I made a final push, trying to speed up to cover the final 2 km, but I had lost the elk trails, and my progress over the boulders and giant fallen trees was painfully slow. It didn’t take long to realize the extra effort was in vain – there was simply no way I could get to the lake before dark, and I needed to find a place to camp.

By 8:00 p.m. it was getting dark under all those clouds and trees, and I was getting desperate. I was soaked, cold, and I still hadn’t seen a flat place larger than a dinner plate. I really didn’t want to spend the night sitting upright in the forest.

I had run out of water hours earlier, so before I could stop for the night I needed to head back to the river and, and as luck would have it, when I reached the river there was a flat spot at the base of a giant tree on the riverbank. The tree was leaning slightly, so it even provided a tiny patch of shelter from the rain.

I quickly removed my backpack to retrieve my water bag, and that’s when I saw a large rip in the mesh back pocket – worse, one of my paddle blades was missing! I had shoved the blades into the pocket the same way I had done every day to this point, trusting the elastic mesh to hold them in place, but one of them must have caught on a branch as I bushwhacked and somehow been pulled out of the pocket without me noticing. It had been several hours since the last time I had removed my backpack, and the paddle blade could have fallen out at any time since then, making the chances of finding it near zero. What a disaster! The only way to get to a town without retracing my steps through the park (including all the hellish hours of bushwhacking and route finding I had just done) was to continue on to Donner Lake and then paddle 6.5 km (4 miles) to its far end. The shores around the lake are extremely steep – mostly cliffs that rise straight out of the water and climb up hundreds of meters to some of the most challenging peaks on the island (e.g. Mt. Colonel Foster) – so hiking around it would be impossible. Without a paddle, I would be screwed.

“One problem at a time,” I told myself before I could go too far down the road of imagining the difficulty of whittling a new paddle blade from a piece of wood, and I pushed the panic back. At this moment I needed water, shelter, dry clothes, and hot food most of all; I would deal with the paddle problem later.

I climbed down the riverbank to fetch water, and when I returned to my backpack, I pulled out my tent and began setting it up. In the process, I turned around and was confused to see my one remaining paddle blade lying on the ground a little way away, in a spot where I hadn’t left it.

“What is going on here?” I thought for a moment, and then I turned around, looked at my pack, and realized that the “remaining” paddle blade was still there in its pocket.

I looked back and forth between the two paddle blades, and to say that I was stunned is an understatement. I stood there dumbfounded, unable to believe my reversal of fortune. The paddle blade could have fallen out anywhere since leaving the unnamed lake 7.5 km (4.7 miles) back – how improbable was it that it would fall out just five paces from the place where I finally stopped to camp? What luck!

Now in a better mood, I finished setting up my tent, fired up my stove, and swapped my soaking wet clothes for dry ones as I waited for water to boil.

This day had nearly crushed me, but it was over now and I had a dry place to sleep, warm clothes to wear, and hot food to eat. I lay under my down quilt as I ate in the dark, too tired to care about bears.

Day 17: Ucona River to Ucona Main